Last post was about the different types of feminine horror. I spoke about this with my friend, horror aficionado Glenys Packer, who had a lot of great insight into modern horror and the feminine. So, naturally, I pawned off my blogging responsibility on her, and she knocked it out of the park! I hope you enjoy!

Female suffering has long been as much a staple of the horror genre as haunted houses and axe-wielding killers. From the rape-and-revenge slasher films that became popular in the 60s and 70s, to various adaptations of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, to the terrifying Japanese and Korean horror films that took the US by storm in the early 2000s, viewers have been watching scream queens, final girls and ghosts alike fight fear, trauma and sadness for decades. In so many of these stories, however, even if she survives the female character is left, ultimately, a victim—of spirits, of her attackers, of her own mind—and the viewers are left with a vague sense of ‘how do you come back from that.’ These stories aren’t about recovering, they’re simply about surviving.

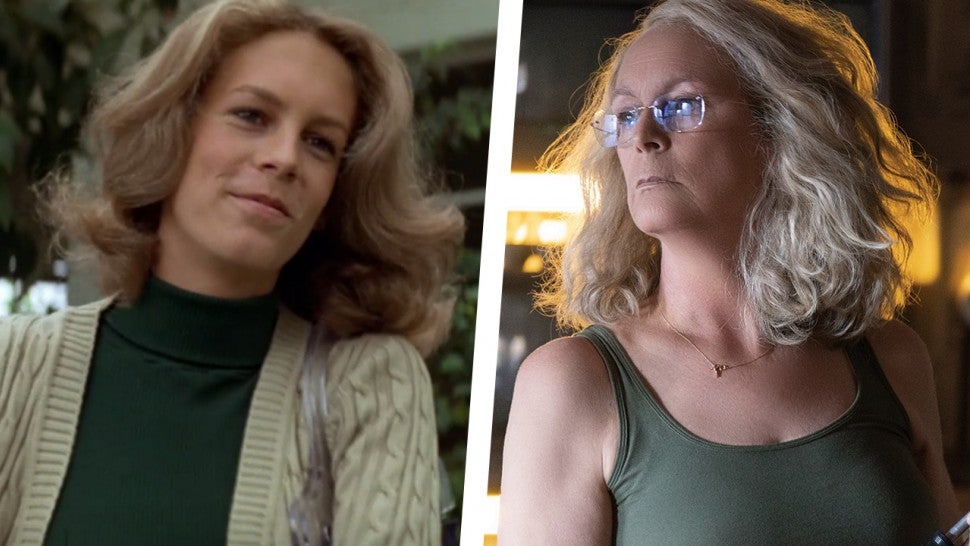

Laurie Strode: 1978 & 2018

Laurie Strode (Jaime Lee Curtis) of the Halloween franchise is a prime example: again and again she survives Michael Meyers, but when we see her in the 2018 sequel Halloween, she has become a paranoid and troubled older woman focused entirely on the man who has been hunting her since she was a teen. Older women are rarely allowed to be badass on screen, so getting to see Curtis at the age of 60 kicking butt and taking names was thrilling—but while watching I couldn’t help but feel sad as well, because the character’s entire life was defined by the trauma inflicted on her. Her family shunned her, she was focused and obsessed only with defeating Meyers. She was alive, but she never moved past that.

In a not insignificant number of more modern films, however, we see female protagonists actively facing the source of their trauma, not simply beating the thing that’s trying to kill them. It’s a twist on the last girl standing trope that leaves us with an actual path to recovery. We see this in Ari Aster’s Midsommar, in Robert Eggers’ The Witch, in the 2018 remake of Dario Argento’s Suspiria. The new generation of female horror protagonists in all three of these examples survive terrible, frightening and heartbreaking ordeals just like their predecessors—but the survival isn’t the ultimate point, the ultimate point is that they heal, and instead find a place where, to quote Midsommar, they “feel held.”

Midsommar, 2019

Horror often operates on a good-vs-evil narrative; you have your protagonist and the “good guys” verses the killer/ghost/demon/cult/etc. In Midsommar Dani is faced with the strange community of Hårga, in The Witch Thomasin is isolated with her family by woods supposedly haunted by a witch, and in Suspiria Susie learns that the teachers at her dance academy are much more sinister than they seem.

Classic horror films might go like this: Dani would find a way to escape the evil commune and walk off into the sunset as a last girl standing, having lost her friends, boyfriend and most of her clothes. Thomasin might find a prophecy that tells her how to defeat the witch. Susie would expose the teachers for what they are and put an end to the evil academy.

Spoilers: that isn’t how any of those movies go.

The Witch, 2015

On top of what we initially perceive as the “evil bad guys” in the films, Dani is also reeling from the tragic loss of her sister and parents in a murder-suicide, Thomasin is fighting the fear and paranoia of her family and the truth that they will turn on her without hesitation, and Susie is alone in a new country, certain only that she’s meant for more than her life in rural Ohio had set her up for.

In none of these instances are the protagonists presented with a handy prophecy or tool for the destruction of the perceived “bad guys,” instead they must navigate the situation on their own, and in all three cases they wind up realizing that what they thought was evil was actually what they were looking for all along. This, in many ways, is an exact opposite to the last girl standing character arc in revenge films like I Spit on Your Grave, or slashers like Texas Chainsaw Massacre or Halloween.

At the end of Halloween Laurie is left with the nightmares of what she has lived through, at the end of Midsommar, Dani has found a place where the viewer knows she will heal.

With the #MeToo movement, the fight for transgender rights, the fight for reproductive rights, the push for more intersectional feminism among countless other gender related movements coming to the forefront of people’s minds, it’s not a far leap to see why movies that show women recovering and conquering are becoming more popular. More and more we are aware that it’s not enough to simply punish those who have tormented you. Unlike movies which end, life keeps moving after trauma, there’s always the question of what happens next. Seeing Dani, Thomasin and Susie rise from the ruins of their struggles to positions of joy and power will, for me at least, always feel more cathartic than seeing a woman kill her rapists and then leave me wondering just how many years she’s going to have to spend in therapy and what a toll this will take on her life.

Last girls may survive, but this new wave of horror queens thrive.

Thanks to Glenys for this great walk through! Like her thoughts? Well good news! She has tons more (including fiction and original art)! Check her out on tumblr and Twitter!